While perusing this reprint of the 1861 edition of Mrs. Beeton's

Book of Household Management

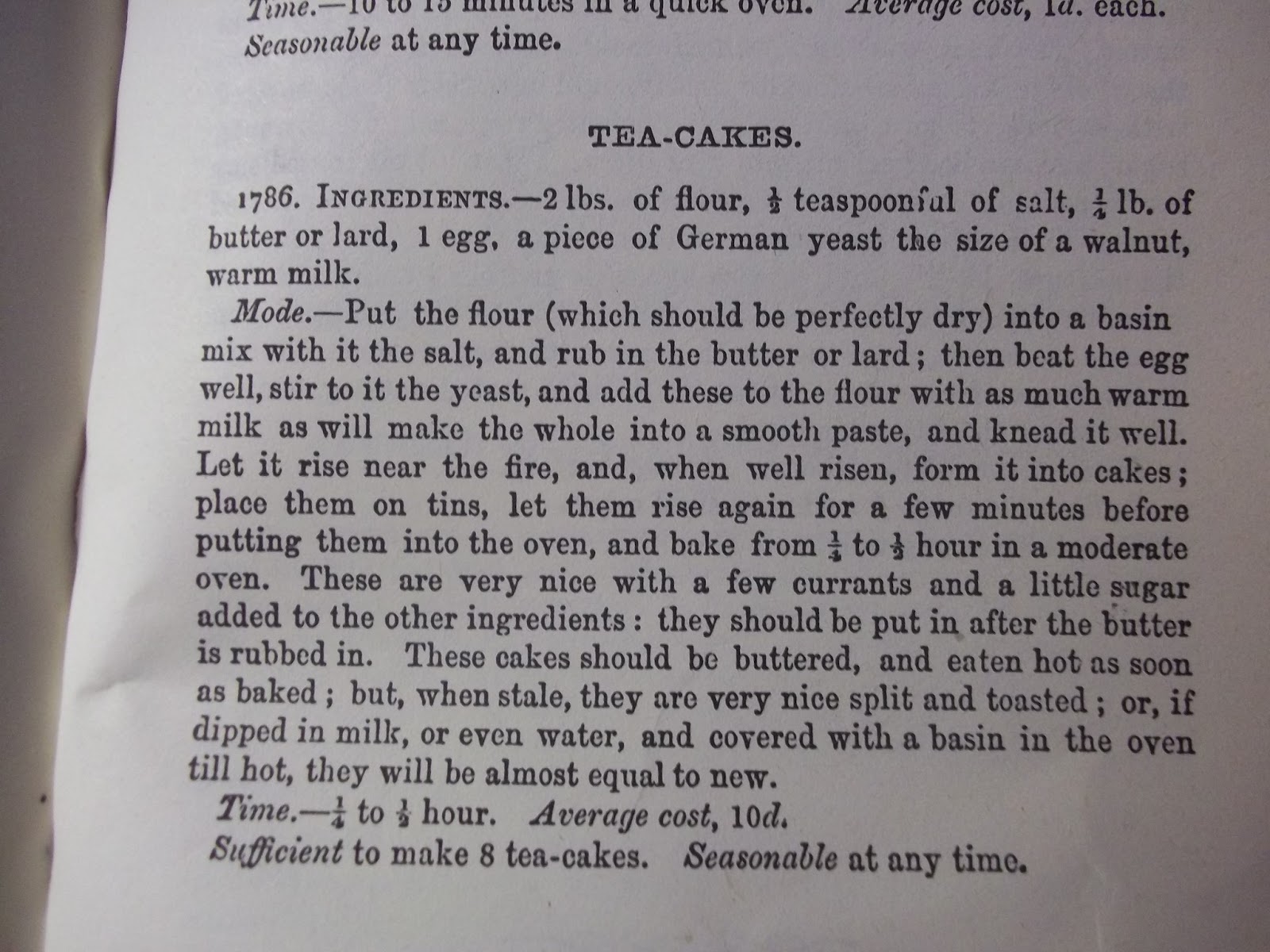

I found this recipe for tea cakes that looked easy enough to recreate and thought would be nice for a picnic that Amy and I were planning to take.

Unfortunately, I wound up sick when we had the picnic planned and noticed (late) that they were best served fresh out of the oven, so they became breakfast on Sunday instead. (One disclaimer- I had it in my head that tea cakes should be of a reasonable personal size and made them about the size of a biscuit but in hind sight, I realized that Mrs. Beeton was getting only eight cakes from this large recipe. I only made a quarter of this recipe and wound up with six, so she was apparently intending for them to be much larger.)

The main aspect I had to be careful about adapting correctly to my modern oven was the baking temperature being referred to only as "moderate." I thought I remembered that being more or less 350 deg. but to be sure, I jumped ahead in time briefly to reference this (original) book I have from 1924:

While recipes arranged in the way we are used to now (with an ingredient list, baking temp., etc.) were not very new by this point, this was still a transitional period for cookbooks. I also have one from 1920 where the recipes are written basically the same way as Mrs. Beeton's. The valuable thing about this book for projects like I was working on is that it combines the old descriptions for oven temperature (e.g. "moderate") with a specific temperature below the recipe. For example:

This makes cross referencing between the descriptions and specifics of oven temperature possible. "Moderate," however, ranges from 300 deg. to 375 deg. in this book, though, so some guess work is still required. In the end, I settled on 350. Converting pounds to cups, the "German yeast" to something more readily available, and doing only one quarter of the recipe to make it a more manageable experiment, the ingredient list became:

1 2/3 Cup Flour

1/8 tsp. Salt

2 Tbsp. Butter (softened)

1 egg (beaten)

1/2 Tbsp. Active Dry Yeast

1/2 Cup (give or take) warm milk

The best results will come from leaving the butter out for 1 1/2-2 hrs before mixing to come to room temperature, then beating it with a fork rather than microwaving or otherwise melting.

Combine the flour and salt, then work in the butter with a fork. Dissolve the yeast in the warm milk (may take more or less- use enough to make a soft, smooth, but not too sticky dough) and add the milk, yeast, and egg to the rest of the ingredients. Knead and cover. Leave to rise until doubled. An easy way to make this part of your breakfast is to mix it just before bed and leave it to rise overnight.

Once risen (or in the morning) preheat your oven to 350, make the dough into biscuit-sized cakes, place on a cookie sheet lined with parchment paper, and leave for 15 minutes or so to rise a bit more.

Bake for 15-20 minutes. Serve soon after coming out of the oven with butter and/or preserves. We found them to be VERY good!

Our simple bread with coffee and tea breakfast would not at all have been considered a full breakfast in Victorian England. More on that later!

Yours &c.,

The Victorian Man

.JPG)

.JPG)